The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) comprises an array of nine radio telescopes around the world: in Chile, the United States, Mexico, France, Spain and Antarctica. By triangulating the data from each, the EHT works like one humongous radio dish, thousands of kilometres across. The signal will not be perfect, but should be enough to capture the bright spot of Sagittarius A* and the black silhouette at its centre.

One of the first things physicists will look at is the shape of the black hole itself. The theory of general relativity predicts black holes to be perfectly spherical, meaning the EHT’s image of the silhouette should appear circular. Any kind of squashed shape could be the first observational disagreement with the accepted orthodoxy – setting up a potential revolution in physics.

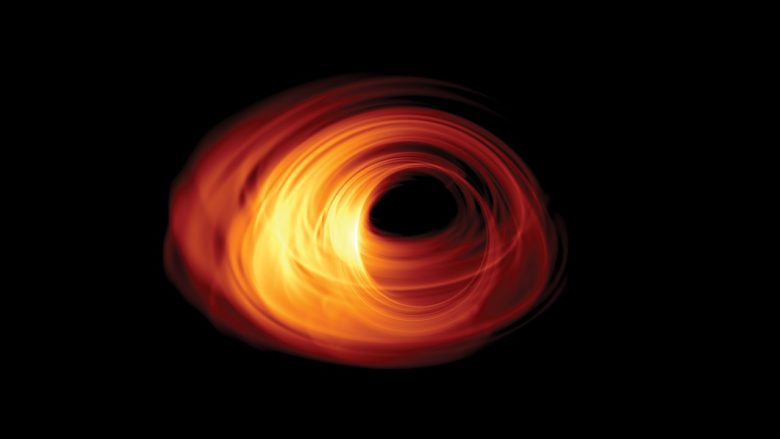

Another mystery relates to the accretion disc, the swirling cloud of material in motion around the hole. How does it heat up? Physicists often describe the process as a kind of ‘friction’ – as if the gas particles rub against one another as they churn around the disc. Yet we know the gas would be too diffuse for direct physical contact. Something else must be going on, perhaps related to strong magnetic fields driving turbulence. Again, direct images could give us the answer.

The evolution of supermassive black holes is tied to the growth of galaxies themselves. To understand these processes, we will need to look beyond the Milky Way. The EHT should be powerful enough to image the supermassive black hole in the centre of the Messier 87 galaxy, in the constellation Virgo, more than 50 million light-years away. Although Messier 87 is more than 2,000 times more distant from us than Sagittarius A*, its black hole is 1,500 times more massive, so it should appear only slightly smaller than Sagittarius A*.

The nine telescopes trained all of their ‘eyes’ on Sagittarius A* in April 2017. Since then, scientists have been compiling the data, rendering the image and comparing it to models of what we expect the black hole to look like. Astronomers and astrophysicists are now anticipating having the first images from the EHT soon.

The result could be the major astrophysical event of 2018, heralding a new age in black hole astronomy – all by looking into the eye of the storm raging at the centre of our galaxy.